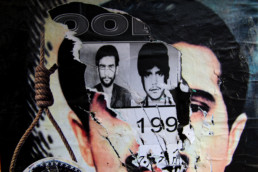

Since 1947 Kashmir’s region has been at the core of a controversial dispute between India and Pakistan, who fought three wars over it in 1947, 1965 and 1999. Moreover, since 1989, an anti- Indian guerilla warfare has erupted in the Indian side of the territory. The separatist insurgency, massively supported by the Muslim majority population, was fuelled by Pakistani army, and deeply rooted in Islamic political ideologies, formally covered by the slogan “Azadi”, meaning freedom in Urdu. The guerilla warfare in the long term was anyway crushed by the brutality of Indian army, and, after 2001, the Azadi movement witnessed a widespread downfall and a general disappointment towards separatist politics, which was interrupted by the 2008-2010 uprisings. Those were basically lead by the generation who had grown up in the conflict environment, that engaged armed forces in intense and recurrent stone-throwing riots. But it is in 2016 that things again radically changed, when Burhan Wani, a charismatic guerilla leader, was killed by Indian soldiers, generating again a massive agitation all over the valley.

Due to the widespread frustration, in the following years, more and more youth from different social background joined militancy, while orthodox Islamic ideologies, mostly linked to Salafia, have started to overcome the traditional Sufi tradition of the valley. At the same time the Hindu right wing Indian government, lead by Narendra Modi, has given free hand to the military forces, and the result, formalized in the operation “All out”, was that 2018, with over 400 people killed by the soldiers, became the deadliest year in the valley since the nineties. Kashmiri conflict still seems to be frozen into a potential ready to explode, where the historical, ideological and political past – mixed with the emotional load conveyed by the logic of martyrdom, the related collective grief and resentment, and the new radical Islamic ideologies – is just ready to blow up into a new season of total warfare.

Kabristan, meaning graveyard in Urdu, is an attempt to represent this paralysed potential, this mixture of anthropological ingredients which look temporary still and static like tombs, but are about to be lit and explode into a new massive stage of violence. The project was developed in Srinagar, the valley’s main city and the core of the Kashmir’s cultural and political history, and it blends different aspects of the relation between people and the pressure of the past, primarily perceived as a deadly and pressurizing atmosphere which intertwines with inner and outer landscapes. It is mainly the calm preceding a predictable storm that I tried to portray throughout a series of visual gravestones, differently balanced in their aesthetic and metaphorical composition, just giving the impression of an intimate tension between the past and the future, grief and anger, introspection and violence, political utopia and bitter realities of the conflict.